FOLDS: Survey Exhibition

-

Featuring works by Alexandra Barth, Rachael Bos, Robert Burnier, Nick Cave, Tim Doud, Crystal Gregory, Dan Gunn, Harmony Hammond, Cameron Harvey, Mie Kongo, Jo Sandman, Alyson Shotz, Malick Sidibé, Samantha Thomas, and Letha Wilson.

The fold forms, informs, and deforms. … With the fold the material transforms itself to contain its subject, allowing access to its content. The fold articulates the art as an object while punctuating its dynamic subject-content. Most importantly, the fold moves us emotionally by the implied and real physicality of its active displacements.

Jeff Perrone. ”Working Through, Fold by Fold”, Artforum, January 1979, pages 44-50.

-

Nick Cave

Forge, 2018

Mixed media including a bronze arm and an array of white handkerchiefs

21.25 x 71.25 x 16.75 inches

-

When they appear in or as works of art, the form of the fold both produces and expects degrees of fidelity, resolution, and sentience. Compositionally, folds delineate and generate movement and energy, with a keen sense of suggested accuracy. This sense of volume then renders qualities of resolution, sharpening the image or object as it relates to the body, gravity and weight. The physicality of and by the fold seems to arrest a moment of intimacy somewhere between the depiction of the thing and how the thing is depicted, as if the folds are emotional repositories of narratives of becoming and creating. Where the fold expects a degree of fidelity, resolution, and sentience is the foundational necessity of specific qualities of a fold to represent and define. For the artists in FOLDS, where the form is investigated, interrogated, and appreciated, the symbolic and effective potential for the fold becomes expansive.

-

-

Alexandra Barth

Carpet Roll, 2023Acrylic on canvas

63 x 47.25 inches -

Depicting draped, folded, or crumpled materials in interiors, Alexandra Barth’s (New York) paintings exhibit a subtle but poignant visual struggle of the distinction between space and place. Beginning with photography, Barth then begins on a smaller canvas only to create the final layer on a larger canvas. Using airbrush, she accentuates design elements in an interpretive scene, a dynamic interplay of light, shadow, and texture in private interiors. Uninhabited, these images evoke a mysterious past that subtly merges with the sensibility of memory, creating a beautiful dance between the tangible and ephemeral.

-

-

-

-

-

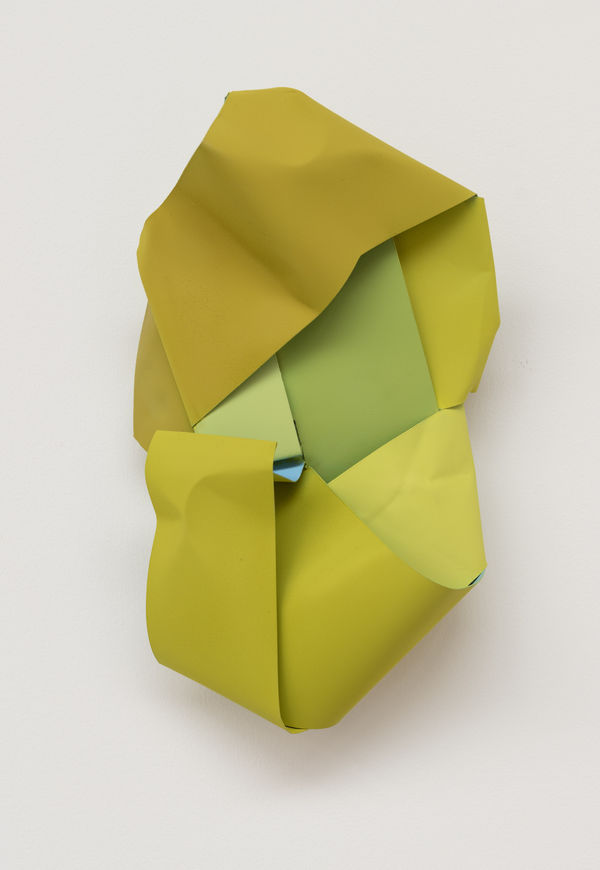

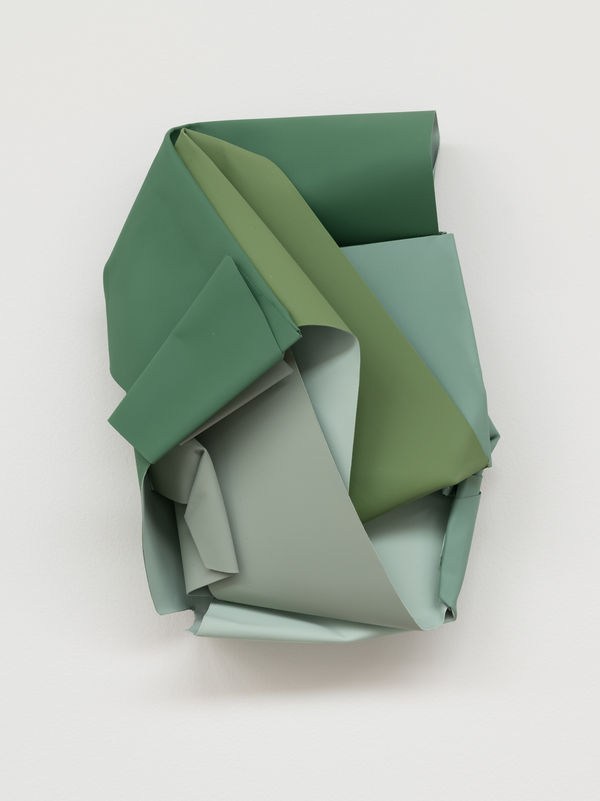

Alyson Shotz

Alloys of Moonlight #10, 2023Paint on hand-folded aluminum

72 x 48 x 7 inches -

-

-

-

-

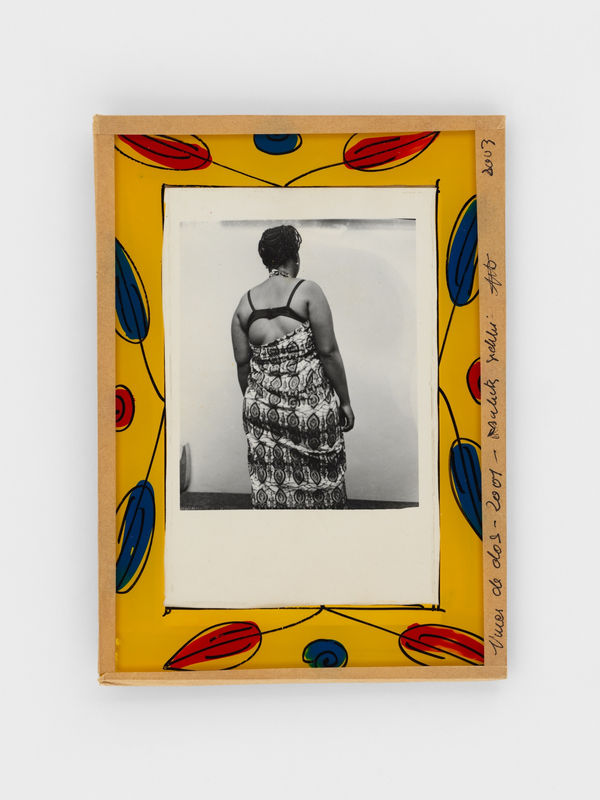

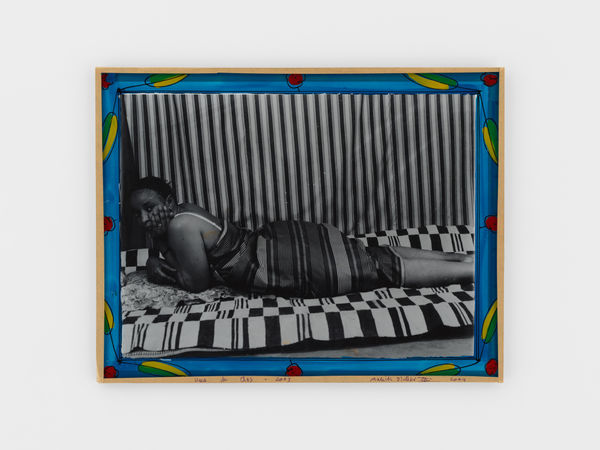

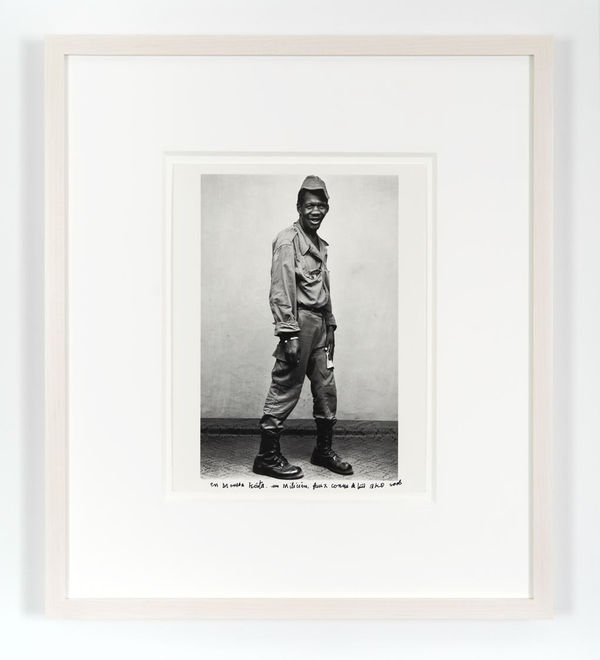

Malick Sidibé (b. 1935, Soloba, Mali; d. 2016, Bamako, Mali), a renowned Malian photographer, began his career by learning to develop and print negatives while working in a photo supply store in Bamako. His work went on to capture the spirit of Mali's independence, documenting the joy, energy, and optimism of youth culture in a newly liberated nation. Through dynamic scenes of celebration and studio portraits that juxtaposed fashionable subjects with bold, patterned backdrops, Sidibé showcased the cultural vibrancy and self-expression flourishing in post-independence Bamako during the 1960s onwards.

In the Vues de dos series, with patterned and colorful framing, the models engage with the camera from restful but expressive positions. Though relaxed, she peers beyond her left shoulder, a smile starting to creep into her lips as her dress adjusts to the movement. Romantic lighting captures subtleties in her body's bend across her skin and fabric. -

-

-

Nick CaveForge, 2018Mixed media including a bronze arm and an array of white handkerchiefs21.25 x 71.25 x 16.75 inches

Nick CaveForge, 2018Mixed media including a bronze arm and an array of white handkerchiefs21.25 x 71.25 x 16.75 inches -

-

Cameron HarveyFigure 1: Cor (Rhus Integrifolia), 2021Acrylic and water based urethane on canvas120 x 54 inches

Cameron HarveyFigure 1: Cor (Rhus Integrifolia), 2021Acrylic and water based urethane on canvas120 x 54 inches -

For Cameron Harvey (Chicago), the midline in the human form is the structure for her large paintings. Using her body parts to physically push paint around the unstretched canvases, pigment fades with randomness and a sense of the organic. Once completed, Harvey drapes/hangs the canvas, reinforcing the relationship between her work and the physical space that supports it.

-

-

-

-

-

Dan GunnNocturne Scenery, 2023Acrylic, milk paint, light stable metalized acid dye, and water-based polyurethane on birch plywood and poplar, with nylon cord75 x 63 x 3 inches

Dan GunnNocturne Scenery, 2023Acrylic, milk paint, light stable metalized acid dye, and water-based polyurethane on birch plywood and poplar, with nylon cord75 x 63 x 3 inches -

With folded forms and three-dimensional appendages, Dan Gunn’s (Connecticut) carved draperies often have a strong sense of compositional intentionality and landscape stylization. Gunn’s work interrogates how the Midwestern artistic identity, often associated with 'folk' traditions like quilting, pottery, and woodworking, serves as a foundation for constructing notions of authenticity tied to region.

-

-

-

Letha Wilson

Green Leaves Tuck Steel, 2023UV prints on steel, steel frame

30.25 x 24.25 x 3.25 inches -

-

-

Rachael BosA. Pavlova (Petit Sauvage), 2024Oil on linen14 x 11 inches

Rachael BosA. Pavlova (Petit Sauvage), 2024Oil on linen14 x 11 inches -

Rachael Bos’s (Chicago) portraiture captures the dynamic movement of the athletic body through carefully rendered clothing. Through precise composition and technique in oil painting, she emphasizes the harmony and structure that exists both in nature and the human form.

-

-

Samantha Thomas

Gardenia, 2024Acrylic on canvas over panel

36.5 x 36 inches -

-

-

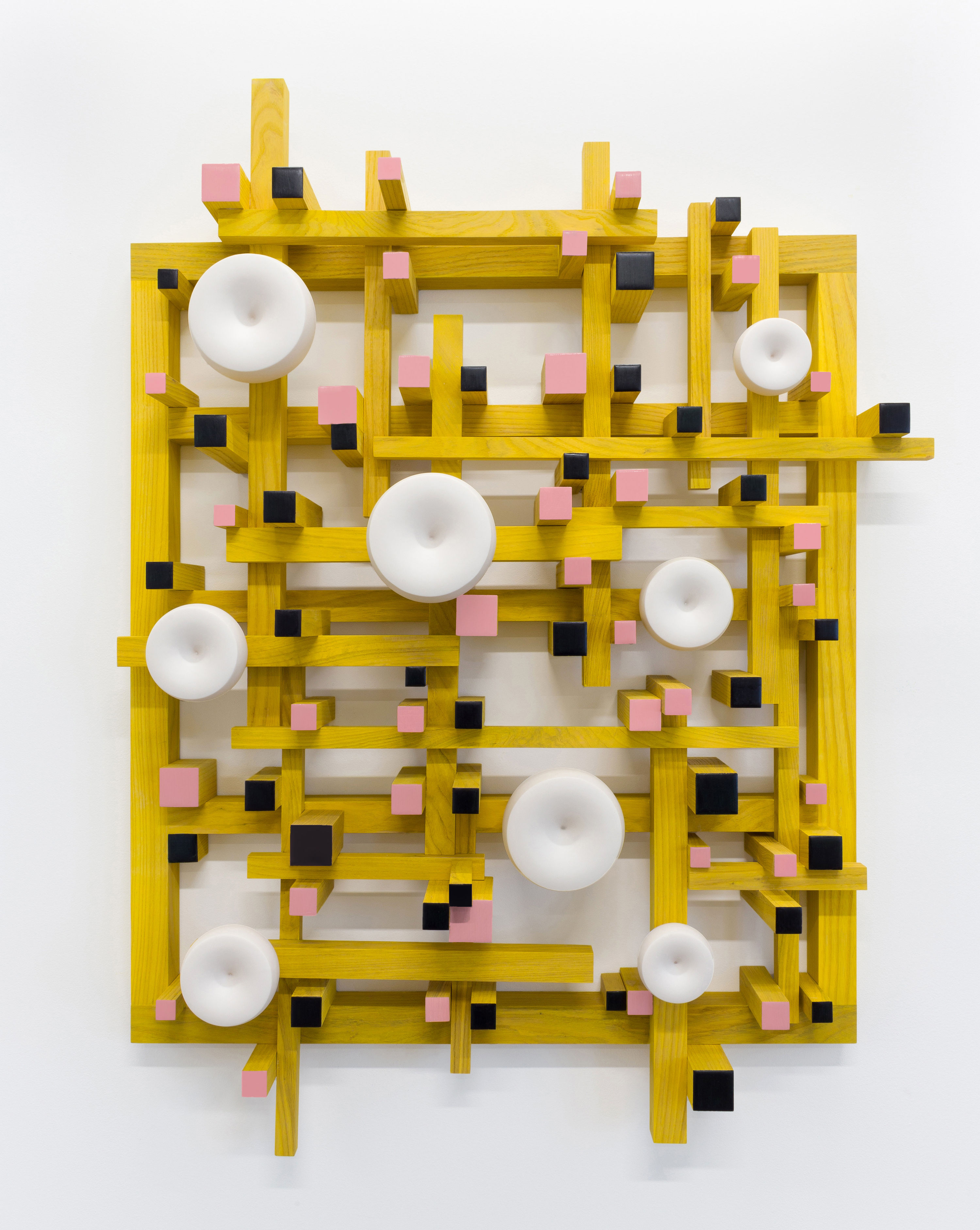

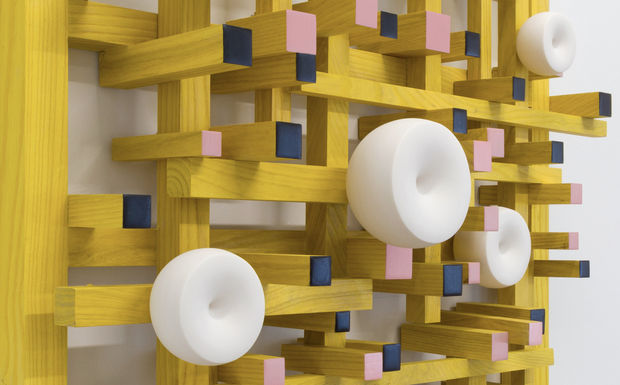

Mie KongoQuarter circle floret, 2024Porcelain, wood, wood stain, oil paint30.5 x 41 x 7.5 inches

Mie KongoQuarter circle floret, 2024Porcelain, wood, wood stain, oil paint30.5 x 41 x 7.5 inches -

-

-

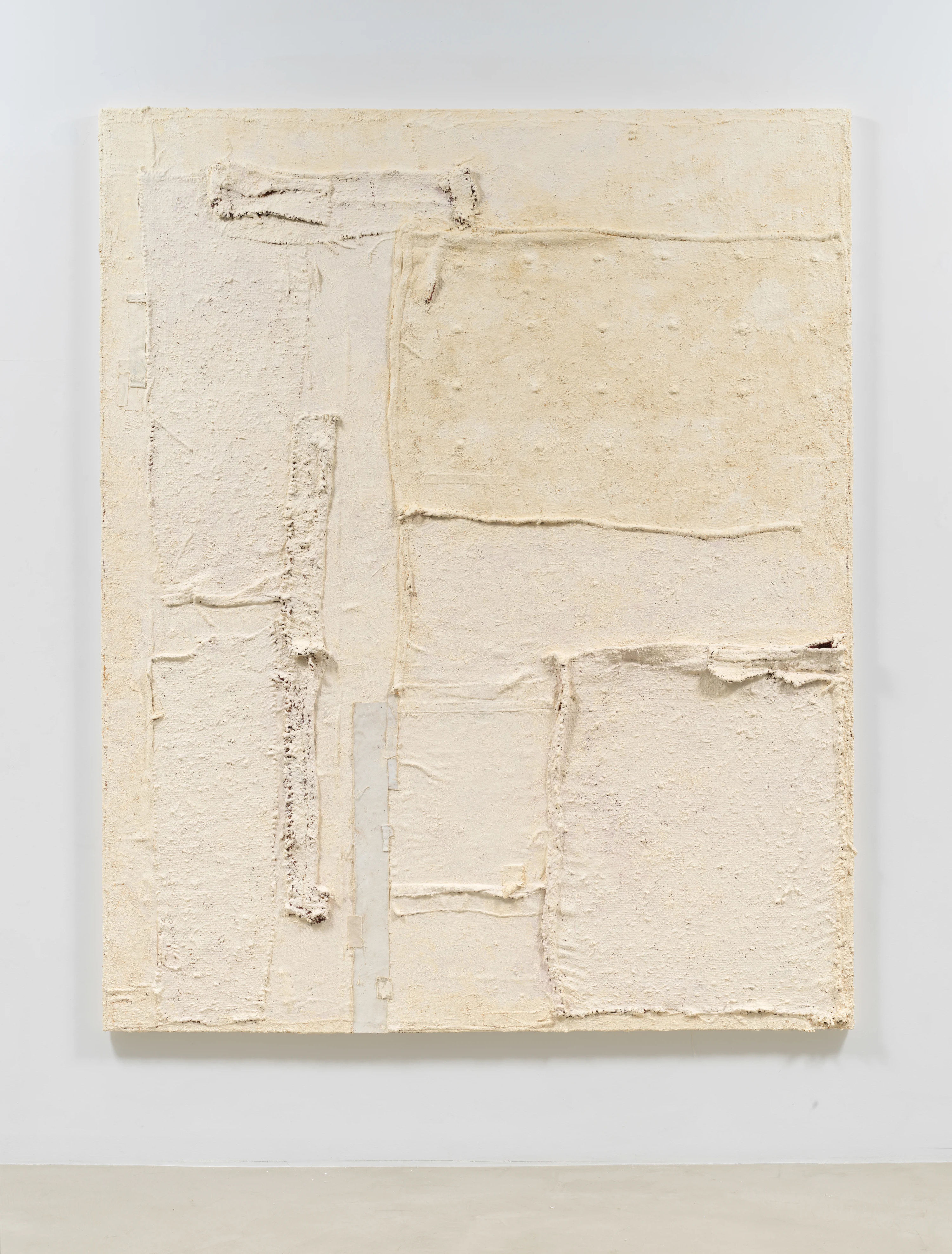

Informed by her background in textile structure, Crystal Gregory's (Kentucky) work challenges traditional material distinctions by incorporating rigid elements such as concrete, metal, and glass, creating an interplay between the pliable and the unyielding. Through this inversion of material expectations, Gregory questions the separation between the collapsible state of textiles and the permanence of architectural forms, suggesting that these opposites are more intertwined than typically assumed.

-

-

Harmony HammondChenille #1, 2016-2017Oil and mixed media on canvas88.5 x 72.5 inches

Harmony HammondChenille #1, 2016-2017Oil and mixed media on canvas88.5 x 72.5 inches -

-

-

-

-

Artists' Biographies

Jo Sandman (b. 1931) A student of both Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell, she was in residence at Black Mountain College with Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly and later worked for Walter Gropius. Trained as a painter, she went on to create innovative drawings, photography, experimental sculpture and installation works, which were exhibited widely and are now in permanent museum collections, including that of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and numerous others. Significant awards include fellowships from the Massachusetts Arts Council and the Bunting Institute at Harvard, as well as grants from the NEA and the Rockefeller Foundation. Over the course of a long career, she has exhibited widely and was featured in the 2022 retrospective Jo Sandman: Traces at the Black Mountain College Museum in Asheville, NC; in a two person exhibition Helen Frankenthaler and Jo Sandman/Without Limits at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, ME; a solo exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Provincetown, MA in 2023/24; and most recently a solo exhibition at Krakow Witkin Gallery in 2024.

Robert Burnier (b. 1969) lives and works in Chicago, IL. He received his MFA from the School of the Art Institute in 2016 and his BS in Computer Science from Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania in 1991. Residencies include Ragdale Foundation (Lake Forest, IL). Recent and upcoming solo exhibitions include Corvi-Mora (London, UK), ANDREW RAFACZ (Chicago, IL), blank projects (Cape Town, SA), Massey Klein Gallery (New York, NY), David B. Smith Gallery (Denver, CO), and The Arts Club of Chicago (Chicago, IL). Group exhibitions include ANDREW RAFACZ (Chicago, IL), New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art at the University of Southern Indiana (Evansville, IN), Corvi-Mora (London, UK), Vacation (New York, NY), Korn Gallery at Drew University (Madison, NJ), Mana Contemporary (Chicago, IL), The Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL), and Elmhurst Art Museum (Elmhurst, IL). Burnier’s large-scale installation Black Tiberinus was on view on Chicago’s riverfront 2018-2019. He has exhibited at art fairs in Chicago, Copenhagen, London, Mexico City, Milan, Miami, and New York. His work has been written about in many publications, including Chicago Tribune, Art Forum, Hyperallergic, Huffington Post, Artnet. Burnier holds the position of Assistant Professor in Painting and Drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL). His work is included in numerous public and private collections.

Samantha Thomas (b. 1980) received her BFA from the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, CA. Her work has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions at Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles/New York; LAXART, Los Angeles, CA; Maccarone Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; and Mike Weiss Gallery, New York, NY. Her forthcoming solo exhibition Chromoception opens at Anat Ebgi in March 2024. Thomas lives and works in Los Angeles, CA.

Crystal Gregory is a sculptor whose work investigates the intersections between textile and architecture. Gregory received her BFA from the University of Oregon and her MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago from the Fiber and Material Studies Department. In 2013 she was awarded The Leonore Annenberg Fellowship for the Performing and Visual Arts. With this grant, she moved to Amsterdam NL where she took a role as Guest Artist at The Gerrit Rietveld Academie of Art. Her work has been exhibited in museums and galleries nationally including Through the Thread at the Rockwell Museum of Art, Devotion/Destruction: Craft Inheritance at Dorsky Gallery Curatorial Projects, Load Barring: The Art of Construction at The Hunterdon Art Museum and Crossover at Black and White Project Space and has been reviewed in publications such as Hyperallergic, Surface Design Journal, Art Critical, and Peripheral Vision Press. Gregory is an Assistant Professor within the School of Arts and Visual Studies at the University of Kentucky and currently shows with Tappan Collective in Los Angeles, CA as well as Momentum Gallery, NC.

Alyson Shotz (b. 1964) received a BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence (1987), and an MFA from the University of Washington, Seattle (1991). Prior to becoming an art student, Shotz briefly studied geology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, focusing on the effects and role of water on Earth—an interest that continues to influence her work. A painter early on, Shotz began in the late 1990s to integrate sculpture into her practice, which explores an interest in nature and the identity of space. In both 1999 and 2010, Shotz was awarded a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant; in 2004, she was the recipient of the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in painting. Her sculptures have been installed in solo presentations at a range of international institutions: Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Wisconsin (2006); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. (2008, 2009); Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus (2010); Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas (2010); Derek Eller Gallery, New York (2011), and the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. (2012). Her work has been shown in multiple group exhibitions, including The Shapes of Space, Guggenheim Museum, New York (2007), and those at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, North Adams (2002); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2008); and Storm King Arts Center, Mountainville, New York (2010). Shotz lives and works in Brooklyn.

Mie Kongo grew up on the outskirts of Tokyo, Japan, and now lives and works in Evanston, IL. She creates multidisciplinary works that have been exhibited nationally and internationally. This includes two solo exhibitions at 65Grand in Chicago, IL, a recent two-person Exposure booth represented by 65Grand at EXPO Chicago, and participation in group exhibitions at NADA Miami represented by The Landing Gallery in Los Angeles, CA. Her other solo and group exhibitions were held at Left field gallery, Los osos, CA; Tri-star Arts, Knoxville, TN; Charlotte Street Foundation, Kansas City, MO; She has completed residencies at Shigaraki Ceramics Cultural Park in Shiga, Japan, and the European Keramic Work Center in ‘s Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. Mie Kongo received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA in Ceramics from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Currently, she serves as a Full Professor, Adjunct, in the Ceramics Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is a recipient of the inaugural Joan Mitchell Fellowship in 2021.

Cameron Harvey (b. 1977) lives and works in Los Angeles. Cameron received her MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA in 2021, her Post-Baccalaureate Certificate in Painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and her BA in Studio Art from Wellesley College. Cameron’s work has been included in solo and group exhibitions both nationally and internationally. She held a teaching assistantship in printmaking and painting at La Scuola Internazionale di Grafica in Venice, Italy, and most recently was an Educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and a volunteer yoga instructor with Prison Yoga + Meditation. Cameron has participated in artist residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, the Lijiang Studio, the Chicago Artists Coalition, and the Ucross Foundation. She presented her first solo museum exhibition at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University in the fall of 2024.

Dan Gunn (b.1980) received an MFA in Painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2007). Recent solo exhibitions include Geary, New York, NY (2024); KMAC Contemporary Art Museum, Louisville, KY (2023); Flyweight Projects, New York, NY (2022); moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2021); The University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL (2019); and Good Weather Gallery, North Little Rock, AR (2019). Gunn has also participated in group presentations at Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH; Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO; Elmhurst Art Museum, Elmhurst, IL; the University of Missouri at Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri; Elephant Gallery, Nashville, TN; University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL; Marine Contemporary, Santa Monica, CA; Art Los Angeles Contemporary, Los Angeles, CA; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL; the Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL; Lloyd Dobler Gallery, Chicago, IL; Columbia College, Chicago, IL; the Poor Farm, Manawa, WI; the Loyola University Museum of Art, Chicago, IL; and the Lubeznik Center for the Arts, Michigan City, IN. Gunn was awarded residencies at the Wassaic Project (2021), University of Arkansas (2019), Anderson Ranch Art Center (2018); Vermont Studio Center (2015); and The Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME (2012). Public collections include the DePaul University School of Music, Chicago, IL; Fidelity Corporate Art Collection; Kentucky Museum of Art and Crafts, Louisville, KY; Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA; Mayo Clinic Corporate Art Collection, Rochester, MN; TD Bank, New York, NY; and The Joyce Foundation, Chicago, IL. Gunn currently lives in New Milford, Connecticut.

Harmony Hammond (b.1944) is an artist, educator, writer, and independent curator. A leading figure in the development of the feminist art movement in New York in the early 1970s, she attended the University of Minnesota from 1963–67 before moving to New York in 1969. She was a co-founder of A.I.R., the first women’s cooperative art gallery in New York (1972) and Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art & Politics (1976). Since 1984, she has lived and worked in northern New Mexico, teaching at the University of Arizona, Tucson from 1989–2006. Her work was included in the 2024 Whitney Biennial: Even Better Than the Real Thing and is included in Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction organized by the National Gallery of Art, traveling to the Museum of Modern Art, NYC (April 20 – September 13, 2025) and Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art originating at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, traveling to the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (September 14, 2024 – January 5, 2025). It was also included in major exhibitions such as Women in Abstraction: Another History of Abstraction (2021 – 2022); Wack! Art and Feminist Revolution (2007); and High Times/Hard Times, New York Painting 1967-1975 (2006-2007).

Nick Cave received an MFA from the Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield, MI (1989) and a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute, MO (1982). In Fall 2011, Cave had two concurrent solo exhibitions in New York, NY at Jack Shainman Gallery and Mary Boone Gallery. Cave was also included in group exhibitions this past Fall, such as 30 Americans: Rubell Family Collection, at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC, and the Prospect.2 Biennial, taking place throughout New Orleans, LA. His solo traveling exhibition, Meet Me at the Center of the Earth—organized by the Yerba Buena Art Center, San Francisco, CA—will be on view at the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, VA through January 2012. Cave has a forthcoming major presentation of his work scheduled for the Tri Postal in Lille, France, in late 2012. His work is held in the following distinctive public collections: the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY; Crystal Bridges, Bentonville, AR; the Detroit Institute of Arts, MI; the High Museum, Atlanta, GA; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL; the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA; and the Seattle Art Museum, WA; among others. Cave has received several prestigious awards including the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award (2008), Artadia Award (2006), the Joyce Award (2006), Creative Capital Grants (2002, 2004, and 2005), and the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award (2001). Cave lives and works in Chicago, IL where he serves as Professor and Chairman of the Fashion Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Tim Doud graduated from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago with an M.F.A in Painting and Drawing. He also attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Skowhegan, Maine. Doud has exhibited his work at Hemphill Artworks, Washington, DC Curator's Office, Washington, DC, Galerie Brusberg, Berlin, Germany, Art Basel, Basel, Switzerland, MC Magma, Milan, Italy, Priska Juschka Fine Art, NYC, RAYGUN, Toowoomba, South Queensland, Australia, Mono Practice in Baltimore, MD and the New Bedford Museum of Art. His work has also been included in exhibitions at PS1 (MOMA), NYC, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Artists Space, NYC, the Frye Art Gallery, Seattle, WA, the Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA, Kemper Contemporary Art Museum, Kansas City, MO, and the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. He has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts (Arts Midwest), the Pollock Krasner Art Foundation, and the DC Commission for the Arts and Humanities and has participated in residencies at the Banff Centre, Alberta, Canada, the Sharpe/ Walentas Studio Program, NYC and the Golden Foundation, New Berlin, NY. Commissions include the State Department’s Art in Embassies Program, in Niamey, Niger, Africa. Letha Wilson (b. 1976) was raised in Greeley, CO (US). She currently lives and works in Craryville and Brooklyn, NY (US). She earned her BFA from Syracuse University, NY (US) in 1998, and an MFA from Hunter College, NY (US) in 2003. Residencies include The MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, NH (US), University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV (US), Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Madison, ME (US), The Yaddo Foundation, NY (US), Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, NE (US), and Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, CA (US). Wilson has recently participated in group exhibitions at Frosch & Co., New York, NY (US); the New York Public Library, New York, NY (US); The Henie Onstad Triennial for Photography and New Media, Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden (NO); MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA (US); MACRO Museo d’ Arte Contemporanea, Rome (IT); Essl Museum, Klosterneuburg (AT); Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, NE (US); Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY (US); Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, NY (US); and the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, CT (US).

Malick Sidibé's (d. 2016, Mali, Africa) magnificent portraits of sweeping personal and cultural changes in post-colonial Africa have been celebrated around the world. Positioned at the junction of Malian independence in 1960 and a period of rapid modernization, his works bear witness to the joy, insouciance and confidence of Africa's youth revolution. Since the initial world premiere of his work in 1997, Sidibé received the the Venice Biennale's Lifetime Achievement Award (2007), Hasselblad Award for Photography (2003) and the International Center of Photography's Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement (2008). His work has been exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery (London), Fondation Cartier (Paris), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Corcoran Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), the Armand Hammer Museum (Los Angeles) among others and can be found in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Museum of Modern Art (New York), SFMoMA (San Francisco), Birmingham Museum of Art, Studio Museum of Harlem, High Museum of Art (Atlanta), International Center of Photography (New York) and Moderna Museet (Stockholm).

Alexandra Barth (b. 1989) received her degree from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava in 2013. A selection of solo exhibitions have been held at Phoinix, Bratislava, Urban gallery, Pescara , Hotdock project space, Bratislava, and Chris Sharp, Los Angeles. Recent group exhibitions include Like a picture, Photoport, Bratislava, The Elevator, Temporary Parapet, Bratislava and MDŽ, White&Weiss, Bratislava. Rachael Bos (b. 1999) is a Chicago based artist that makes oil paintings exploring athleticism. Rachael received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2021. Her work has been shown at De Boer (LA), Nathalie Karg Gallery (NYC), No Gallery (NYC), The Hole (NYC), Sulk Chicago (Chicago IL), Mickey Gallery (Chicago IL), Apparatus Projects (Chicago IL), and Galerie Rolando Anselmi (Rome, Italy).

Header image: Jo Sandman, Untitled (Folded Linen), 1974 (ca.), Folded fabric, linen, 17.5 x 24 inches

![Jo Sandman Untitled [#35] (Folded linen, brown), 1973 (ca.) Folded fabric, linen 44 x 39 inches (approximately)](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/secristbeach/images/view/26615a234d3220049945e4cfb37e4787j/secrist-beach-jo-sandman-untitled-35-folded-linen-brown-1973-ca..jpg)